HAEMOPHILUS

BORDETELLA

BRUCELLA

PASTEURELLA

LEGIONELLA

HAEMOPHILUS

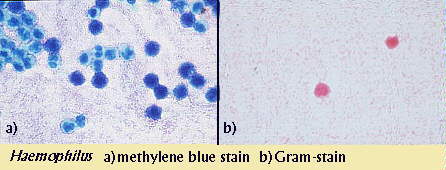

The Haemophilus genus represents a large group of Gram-negative rods

that like to grow on blood agar. The blood provides two factors which many

Haemophilus species require for growth: X factor and V factor. Sometimes

Haemophilus is cultured using something called the "Staph streak"

technique. In this procedure, both Staphylococcus and Haemophilus

organisms are grown together on blood agar. Haemophilus colonies will

usually form small colonies called "satellites" around Staphylococccus

colonies because Staph can provide the necessary factors required for

optimium Haemophilus growth. Morphologically, Haemophilus bacteria

usually appear as tiny coccobacilli under the microscope, but they are included

with the Pleomorphic bacteria because of the many shapes they assume. A

methylene blue stain of a smear can also help with identification.

Haemophilus species are classified by their capsular properties into six

different serological groups, (a-f). Species which possess a type b capsule are

clinically significant because of their virulent properties.

H. influenzae

Infection by H. influenzae is common in children and its name may lead

you to conclude that it is the causative agent of the flu. Actually, this

bacterium causes a secondary respiratory infection that usually inflicts those

who already have the flu. This species may exist with or without a pathogenic

polysaccharide capsule. Although both strains occur as normal flora of the nose

and pharynx, they can confer severe illness in patients that are

immunosuppressed or that have pre-existing respiratory ailments. Strains that

lack the capsule usually cause mild localized infections (otitis media,

sinusitis), as opposed to the type b encapsulated strain of H. influenzae

that can cause several serious infections. Most of these infections occur in

unvaccinated children less than five years of age because they have not yet

formed antibodies against the bacterium. H. influenzae infection can lead

to a variety of diseases:

- Meningitis- H. influenzae is the most common cause of

bacterial meningitis in children between the ages of five months and five

years. The initial respiratory infection can spread to the blood stream and

eventually the central nervous system. A stiff neck, lethargy, and the absence

of the sucking reflex are common symptoms in infected babies. A vaccine is

available, but is not always effective in very young children. Adult

meningitis is much less common and usually only occurs in those predisposed to

illness.

- Epiglottitis- H. influenzae is the number one cause of this

potentially fatal disease, which may cause airway obstruction in children

between the ages of 2 and 4.

- Haemophilus infection has also been associated with chronic

bronchitis, pneumonia, bacteremia, conjuctivitis, and a host of other

illnesses.

For serious infections, third generation cephalosporins are

the drug of choice. Resistance may develop when ampicillin is used in treatment.

OTHER SPECIES

H. aegyptiusThis bacterium is biochemically identical to H.

influenzae. It is known to cause pinkeye (conjuctivitis) and is spread very

easily, especially among children.

H. ducreyiChancroid, a sexually transmitted disease

characterized by painful genital ulcers, is associated with this bacterium.

H. ducreyi does not require the V factor for growth nor does it ferment

glucose.

BORDETELLA

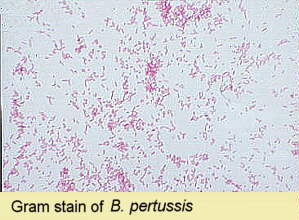

Bordetella organisms are small, Gram-negative coccobacilli which are

strict aerobes. The three species of this genus vary in motility and certain

biochemical characteristics. The most important species in this genus is B.

pertussis, the organism which causes whooping cough. This highly

contagious bacterium makes its way into the respiratory tract via inhalation and

subsequently binds to and destroys the ciliated epithelial cells of the trachea

and bronchi. It does this through the use of several toxins:

- Pertussis toxin- an exotoxin which enters target cells and

activates their production of cAMP, a molecule that acts as a second messenger

in cell protein synthesis regulation

- Tracheal cytotoxin- causes ciliated epithelial cell destruction

- Hemoagglutinin- a cell surface protein which helps the bacterium

bind to the host cell surface

Under the

microscope, Bordetella are often bipolar stained and appear singly or in

pairs. The best method for isolation of Bordetella is on Bordet-Gengou

agar or Regan-Lowe medium. Under the

microscope, Bordetella are often bipolar stained and appear singly or in

pairs. The best method for isolation of Bordetella is on Bordet-Gengou

agar or Regan-Lowe medium.

There are about 5000 cases of whooping cough per year in the United States,

usually afflicting children less than a year old. A vaccine has reduced the

incidence of this disease one hundred fold since its introduction! Despite this

extraordinary rate of eradication, controversy exists regarding the safety of

the vaccine. Antimicrobial therapy for whooping cough usually consists of

erythromycin.

Two other species of Bordetella are also of clinical importance. B.

parapertussis is a respiratory pathogen that can cause mild pharyngitis.

This bacterium is similar to B. pertussis but lacks some of the toxins

which make its sibling so nasty. Biochemical testing can easily differentiate

the two species. Bordetella bronchiseptica is usually a cause of

pneumonia, otitis media, and other respiratory infections in animals. It is

seldom known to be a human pathogen. Its motility makes it easy to distinguish

from the other two organisms in this genus.

| DIFFERENTIATION OF BORDETELLA SPECIES |

|

Growth on

Blood Free Peptone |

Urease |

Nitrate

Reduction |

Motility |

Citrate |

| B. pertussis |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| B. parapertussis |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

| B. bronchiseptica |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

BRUCELLA

Brucella is another strictly aerobic, Gram-negative coccobacillus

which causes Brucellosis. This organism is sometimes carried by animals and only

causes incidental infections in humans. The four species of this genus that can

infect humans are named for the animal which they are most commonly found: B.

abortus (cattle), B. suis (swine), B. melitensis (goats),

B. canis (dogs). The cattle and dairy industries seem to be the primary

source of infection in the United States. Brucella can enter the body via

the skin, respiratory tract, or digestive tract. Once there, this intracellular

organism can enter the blood and the lymphatics where it multiplies inside

phagocytes and eventually cause bacteremia (bacterial blood infiltration).

Symptoms vary from patient to patient but can include high fever, chills, and

sweating. Afflicted individuals are usually treated with streptomycin or

erythromycin.

PASTEURELLA

Organisms of the genus Pasteurella are Gram-negative, non-motile,

facultatively anaerobic coccobacilli. Unlike most of the pleomorphic organisms

we have spoken of, Pasteurella is not an intracellular parasite. P.

multocida is the species which most commonly infects humans. Although most

members infect animals, humans can acquire the organism from dog or cat bites.

Patients tend to exhibit swelling, cellulitis, and some bloody drainage at the

wound site. Infection may also move to nearby joints where it can cause swelling

and arthritis (not to mention a lot of pain). Fortunately, P. multocida

is susceptble to penicillin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol. For

identification, this organism can be cultured on chocolate agar and can produce

a really foul odor.

LABORATORY INDICATIONS:

- Oxidase +

- Non-motile

- Catalase +

- Non-hemolytic (some are beta-hemolytic)

- Indole +

- Ornithine decarboxylase +

LEGIONELLA

The first discovery of bacteria from genus Legionella came in 1976

when an outbreak of pneumonia at an American Legion convention led to 29 deaths.

The causative agent, what would come to be known as Legionella

pneumophila, was isolated and given its own genus. The organisms classified

in this genus are Gram-negative bacteria that are considered intracellular

parasites. They grow well on buffered charcoal yeast extract agar, but it takes

about five days to get sufficient growth. When grown on this medium, Legionella

colonies appear off-white in color and circular in shape. Laboratory

identification can also include microscopic examination in conjunction with a

direct flourescent antibody (DFA) test. Since the initial discovery many species

have been added to the Legionella genus, but only two are within the

scope of our discussion: L. pneumophila and L. micdadei.

LABORATORY INDICATIONS:

- Motile

- Urease -

- Catalase +

- Nitrate -

- Gelatinase +

L. pneumophilaL. pneumophila is the bacterium associated

with Legionnaires' disease and Pontiac fever. Respiratory transmission of this

organism can lead to infection, which is usually characterized by a gradual

onset of flu-like symptoms. Patients may experience fever, chills, and a dry

cough as part of the early symptoms. Patients can develop severe pneumonia which

is not responsive to penicillins or aminoglycosides. Legionnaires' disease also

has the potential to spread into other organ-systems of the body such as the

gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system. Accordingly, patients

with advanced infections may experience diarrhea, nausea, disorientation, and

confusion. The 1200 or so cases of Legionnaires' disease per year in the United

States usually involve middle-aged or immunosuppressed individuals. Pontiac

fever is also caused by L. pneumophila but does not produce the severity

of the symptoms found in Legionnaires' disease. The flu-like symptoms are still

seen in Pontiac fever patients but pneumonia does not develop and infection does

not spread beyond the lungs. Most L. pneomophila infections are easily

treated with erythromycin.

LABORATORY INDICATIONS:

- Beta-lactamase +

- Hippurate hydrolysis +

L. micdadeiL. micdadei is the second most commonly

isolated member of Legionella. This bacterium can cause the same flu-like

symptoms and pneomonia which characterize an L. pneumophila infection.

Unlike its relative, L. micdadei is sensitive to the penicillins because

it does not produce beta-lactamase.

LABORATORY INDICATIONS:

- Beta-lactamase -

- Hippurate hydrolysis -

- Acid fast

|